Prairie Crocus

Anemone patens – The genus name Anemone comes from the Greek word for “wind.” Anemone plants are known as windflowers, because it was believed that they blossomed only when the wind blew in springtime.

Other names

- In Latin: Anemone patens L. var wolfgangiana (Bess.) Koch, alsoPulsatilla ludoviciana, Pulsatilla patens

- In English: Pasque flower, prairie anemone, prairie smoke, wind flower

- In French: Anémone pulsatille, pulsatille de Pâques

Taxonomy

RANUNCULACEAE (Buttercup) family

This furry little perennial is actually not a crocus, which is in the Lily family; it’s really an anemone, in the Buttercup family.

Description

As soon as the snow melts, you will want to start looking for this “harbinger of spring”! The prairie crocus has pale blue or purple flowers arising from the woody rootstock that appear very early in spring. The whole plant is covered with woolly-white hairs.

- Flowers: The flowers are about 4 cm (1 1/2 in.) in diameter, each with five to seven petal-like sepals, and many pistils and bright yellow stamens. (Like all anemones, prairie crocus does not have true petals. The blue or purple-coloured parts that look like petals are actually modified sepals.) When folded, the outer surface of the sepals appear covered in white woolly hairs. The flowers are open during the day but close at night.

- Seeds: After the flower fades and sepals fall off, the pistils develop into a shaggy cluster of seeds, each seed with its own feathery plume.

- Leaves: The leaves, gray-green and much divided, don’t appear until the flower fades.

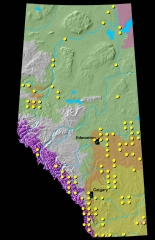

Distribution in Alberta

Prairie crocus grows in northern latitudes more or less all around the world. It is common in eastern Russia and Asia, but there are wide gaps in its distribution in Europe. It is widespread in North America, appearing from Canada south to New Mexico. In Canada, it occurs in the Yukon and Northwest Territories, and from B.C. east to Manitoba. Its prairie population has declined greatly since pioneer days because it grows in native prairie sod, most of which has been ploughed or cultivated.

Habitat

Prairie crocus grows on the prairie and in dry, open woods, often on sandy soils. It prefers sunny, hot, dry areas. It is often found together with yarrow and golden bean. In the dry, southern prairies, it is mainly found on north-facing slopes. In northern Canada, it more often appears on warm, south-facing slopes.

How to Observe

- As much as possible, walk only on paths, as prairie crocus buds are easily damaged by feet.

- When a prairie crocus site is located, mark off an area approximately 1 m x 1 m (3 x 3 ft.) using small rocks or sticks.

- Record the dates when the prairie crocus patch reaches first and full bloom, defined as follows:

- First bloom: when the first flowers are open in the observed plants

- Mid bloom: when most blooms are open, very few are still emerging from the soil, and the stem between the flower and the stem leaf is only about 3 cm long.

Note: You may find that deer or ground squirrels eat your flowers! If so, please report this information under “Comments” on the data form.

Life Cycle

Prairie crocus is a very early-flowering plant, occasionally blooming in south-facing meadows and warm parts of the prairies as early as March. This plant first emerges from the ground as a hairy flower bud; the furry leaves are hard to see at this point. When the purple sepals open they reveal bright yellow stamens inside. The flowers open in sunshine and close again in the evening and in cloudy weather.

As the days go by, the flower stem beneath the leaves lengthens. After pollination, the stem between flower and leaves grows longer, too, pushing the developing seed head up 10 cm – 40 cm (4 – 16 in.) above the ground. At the same time, the leaves fully expand. The flowering period lasts for about two weeks. The long, feathery seeds ripen in May to July, depending on latitude and altitude, and relative earliness of that year. Then the aboveground parts of the plant dry up and disappear (over the summer). The feathery seeds and the long, mature flowering stem are special adaptations to assist in wind-dispersal of the seeds.

To investigate: do stigmas in the flower centre turn pink once pollinated?

Phenology

On average, prairie crocus starts flowering in central Alberta about the third week of April. At this time, the mountain bluebirds are back searching for nest holes in trees or boxes, big flocks of snow geese are winging north, and aspen poplar is also blooming (catkins on male trees are shedding pollen into the air).

Contact local naturalists to learn when prairie crocus usually starts blooming in your area. What other spring events occur at the same time?

Ecology

Prairie crocus seems to be generally limited to unbroken prairie. It forms a partnership with fungi in the soil, exchanging nutrients. These fungi are important for its success in dry prairie soils. Occasional fires seem to greatly improve growing conditions for prairie crocus, by boosting the supply of nutrients and sunlight when dry grass cover is removed. Two years after a fire, prairie crocuses bloom in much greater abundance (see Range Management, below).

Anemone patens grows very well in a grazed habitat. As the taller-growing and better-tasting grass and forb species in a pasture are removed, prairie crocus increases. The deep roots of the plant live for many years and are not seriously affected by animal hooves. Large clumps of prairie crocus in a grazed pasture may show that the area is overgrazed; that is, it has more cattle than the pasture can support.

The hairs on the prairie crocus make the plant less attractive to livestock, but just in case being hairy isn’t a strong enough defense, the plant has poisonous properties, too! It contains a poisonous alkaloid, an irritant that can cause inflammation and blistering. This irritant can be a problem to domestic sheep when they eat the flowers, but it seems to be ignored by deer, elk and ground squirrels, which eat the prairie crocus in the early spring.

Prairie crocus does well in grazed areas, but fields that are ploughed are a different matter. Prairie crocus is slow to return even to favourable sites after ploughing, perhaps because it needs the fungal partners that only occur in unploughed soils. In one case it took 40 years for prairie crocus to return to a small ploughed section of hilltop in eastern Alberta.

American goldfinches (bright yellow and black birds also called “wild canaries”) visit prairie crocuses in summer, and eat the seeds.

Human Uses/Folklore

Surely one important “use” of the prairie crocus is to “decorate” the prairies in celebration of the arrival of spring! Early settlers called this native anemone the “prairie crocus” because it reminded them of their early crocuses back in Europe. The plant is also called pasque flower because in some areas it tends to bloom at Easter-time.

The poisonous properties of the prairie crocus were used to advantage by First Nations Peoples. A poultice made from the plant was used as a counter-irritant to treat rheumatism or other muscular pains. Prairie crocus was also used to stop nosebleeds and draw out infection in cuts and boils. First Peoples knew the plant was dangerous if taken internally.

According to legend the furry coat was given to the flower to protect it on chilly spring nights. (See “How the Prairie Anemone got its Fur Coat” below) The Blackfoot word “Napi,” the “old man” central to the Blackfoot creation story, also refers to the grayish seed heads of prairie crocus, which appear in early summer.

A Yukon child coined the term “elephant’s Q-tips” for the fuzzy, pointed buds.

This plant is the floral emblem of Manitoba and South Dakota.

Horticulture (Use in the Garden)

This welcome little sign of spring is sometimes difficult to grow in a garden. It can be started from seed collected from the wild, or purchased from growers specializing in native plants and seeds.

Transplanting Native Plants

Please do not attempt to transplant plants from the wild to the garden. Transplantation usually fails (i.e., plants die within a few years), and it contributes to loss of biodiversity in our remaining natural habitats!

Range Management

Like other native prairie plants, prairie crocus often flowers much more abundantly after a fire. Fire removes the dead plant litter, returns minerals to the soil surface, and increases light. In pre-settlement times, small fires could occur all through the year, and native plants are well adapted to fire. Now, as awareness of the importance of fire is increasing, its use as a management tool in natural areas is also increasing.

Safety is a big issue. Fire should ONLY be used under the direction of trained, experienced people who can supervise a controlled burn – and who will accept liability in case the fire gets away and someone is injured, or property is damaged. If permission and expert help is available to manage a burn of your prairie crocus habitat, you may wish to encourage this species by burning every few years – in winter, very early spring, or fall in the Chinook belt.

Quotes

“The name of ‘gosling’ given the downy buds by prairie children is eminently suitable, but the Indian name is even better. The Indians… had a perfect genius for choosing the most poetic and significant name for things about them. ‘Ears of the Earth’ they called these furry ears which, so soon after the snow drifts melt, the prairie thrusts up to listen for the first faint rustle of summer.”

A. Brown. 1970. Old Man’s garden. Gray’s Publishing Ltd., Sidney, B.C.

“Spring comes with a rush in the Arctic. The snow disappears almost overnight; and long before the last drifts have entirely vanished, the first flowers put in an appearance. At the mouth of the Mackenzie Delta, the Pasque-flower or “wild crocus” (Pulsatilla ludoviciana) began growth on May 15, when a thin crust of snow still covered last year’s withered leaves. On May 25, when the ground had dried, the large bluish flowers appeared while the new foliage was still undeveloped. On June 25 some of the seeds had already been dropped.”

A.E. Porsild. 1951. Plant Life in the Arctic. Canadian Geographical Journal.

References

Brown, A. 1970. Old Man’s garden. Gray’s Publishing Ltd., Sidney, British Columbia (reprint available from Lee Valley Tools stores)

Johnson, D., L. Kershaw, A. MacKinnon, and J. Pojar. 1995. Plants of the western boreal forest and aspen parkland. Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton, Alberta.

Johnston. A. 1987. Plants and the Blackfoot. Lethbridge Historical Society, Occasional Paper No. 15. Lethbridge, Alberta.

Kindscher, K. 1992. Medicinal wild plants of the prairie. University Press of Kansas. Lawrence, Kansas.

Marshall, H.H. 1989. Pembina Hills flora. Morden and District Museum, Morden, Manitoba.

Parish, R., R. Coupe and D. Lloyd. 1996. Plants of southern interior British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton, Alberta.

A Blackfoot Legend

How the Prairie Anemone Got Its Fur Coat

Wapee shivered and drew his robe tighter around him. It was cold there on the hillside, but the shiver was more of fear and loneliness, than of cold. Always before he had slept in the tipi of his parents, where his father could protect him.

But at last his father had said, “Wapee is no longer a child. It is time he went to the hills to dream and become a man.”

So here he was, by himself, on a hilltop, with great stars above him, the long line of the mountains still sleeping far to the west and nothing about him but a great emptiness.

The morning before he had set out with a light heart. The snows of winter had but lately melted, the sun was warm; and would he not, that very night, dream a great dream that would change him from the child he had always been to the man he was to be? But now the sky was lit by the coming day and all through the night he had lain, not with bright visions, but with dark space and loneliness and fear.

The mountains turned from dark, cold grey to rosy pink, then to purple and last to shining blue, but Wapee still crouched on the hilltop, motionless and brooding. Three more nights like the one just past and he must return to his father and his friends and tell them that he was not a man but only a coward, whom the Great Spirit had found unworthy even of a dream.

The day grew warm and the feeling of great weariness and failure lifted, as it always lifts in the presence of the warm sun god. Besides, Wapee was no longer alone. He had found a friend. Beside him on the hilltop sat a beautiful flower, as white as the snow that was now resting on the slopes of the far-off mountains, before its summer journey to the north land. The flower opened its heart to greet the golden sun and swayed and nodded to Wapee until his troubled mind was calmed by the peace of the blue mountains and wind-washed prairie grass.

Wapee sat on the hillside watching occasional crows pass back and forth, or a hawk wheel far above him, or listening to the stir of growing things beneath him and thinking grave thoughts. So the day passed.

The mountains turned to rose, then grey. The sun dropped down behind them, leaving to Wapee once more the darkness and the stars, but not emptiness, for now he had a friend, the little white flower, near him.

“Little brother”, he said, “It is cold for such fragile loveliness on a night like this. I will lie close and shelter you with my warm robe, but I must not crush you with my big body.”

So while one part of his mind slept and rested, the other part kept watch over the flower.

When the dark of the night was just preparing to meet the light of the day, the flower spoke. “Yesterday, Wapee, you were sad because you had been afraid. He who never knows fear is a fool. The wise man learns to overcome it and profits by it.”

Wapee sat up with a start and bent over the flower to hear better what it might say but the flower only nodded and swayed in the morning breeze.

All day Wapee pondered on the saying of the flower and next night, when he lay down to sleep, he again sheltered it with his robe of fur. Again, just as Morning Star looked out across the prairie, it spoke.

“You have a kind heart, Wapee. It will lead you to great things.”

Next night, still sheltered under the robe, the flower spoke again. “Wisdom and a gentle heart will make of you a great leader. But when you are bowed with troubles and cares remember that on a nearby hilltop you will find peace and warmth.”

Then Wapee slept and saw, dimly, many visions of what was to come when he should be chief of his tribe and his people happy, contented and prosperous.

Before he rose to go to his people he thought once more of the flower.

“Little brother”, he said, “three nights you have comforted me in my loneliness and brought me visions. Tell me now three of your wishes that I may ask the Great Spirit to grant them to you.”

The flower, nodding, answered. “Pray that I may have the purple blue of the distant mountains in my petals, that men may seek my company and be rested. Second let me have a small golden sun to hold close to my heart, to cheer me on dull days when the sun god is hidden. Last, let me have a warm coat, like your robe of fur, that I may face the cold winds that blow from the melting snow and bring men comfort and hope of warmer winds to follow.”

The Great Spirit was pleased that Wapee’s first thought had been for the flower and his prayers were answered. Now over the hillsides thousands of the descendants of Wapee’s small friend face the cold winds of early spring, with the colour of the distant mountains in their petals, a bright sun in their hearts, and a warm furry robe wrapped securely about them.

By Annora Brown

reproduced with permission, from Old Man’s Garden