Wild Strawberry

Fragaria virginiana; Fragaria vesca – Fragaria is from the Latin “fraga”, the classical name used for the strawberry fruit, referring to its fragrance. The species name Virginiana means “of Virginia”. The common name strawberry is from an old Anglo-Saxon word “streowberie”, perhaps derived from the age-old practice of laying straw around cultivated plants to keep the fruit off the ground, or as a way to describe how the plants are ‘strewn’ across the ground.

Other names

- in Latin: Fragaria virginiana Duchesne/ Fragaria vesca L.

- in English: woodland strawberry is Fragaria vesca, blue-leaf strawberry is another name for F. virginiana

- in French: fraisier de Virginie, fraisier des champs, fraisier sauvage

- In Chipewyn: idziaze (“little heart”)

- In Cree: otehiminipukos (“heart berry”), otihiminipukway (“heart berry plant”)

- In Slave: idzheah

Taxonomy

Rose Family (Rosaceae)

Description

Both species of strawberry described here can be observed for Plantwatch. They look very similar and bloom at about the same time. It is not necessary to identify what species you are observing, as long as it is a wild strawberry. For your interest, differences are described below.

Wild strawberries are perennial herbs that grow from a fibrous root with short rhizomes (creeping roots). They have long, slender, leafless runners that are often reddish in colour. These runners root when they contact the soil, to form new plants.

- Leaves: The leaves are divided into three strongly-toothed, egg-shaped leaflets (leaflets usually 2 to 7cm long). Fragaria viriginiana: The upper leaf surface is bluish-green, the terminal tooth of each leaflet is shorter than its adjoining teeth, and the leaf teeth are blunter.

Fragaria vesca: The leaves are yellow-green on the upper surface, and the terminal leaflet tooth of F. vesca is longer than its adjoining teeth.

- Flowers: Each plant has 2 to 15 small flowers with yellow centres and white petals (7 mm to 10 mm long).

- Fruit: The fruit of the wild strawberry is small (up to 1.5 cm wide), and looks like a miniature version of store-bought strawberries. F. virginiana seeds are sunken in pits on the strawberry surface, and the fruit stem is shorter than the leaves. The seeds of F. vesca sit on the fruit surface, and the fruit stems are longer than the leaves.

Distribution

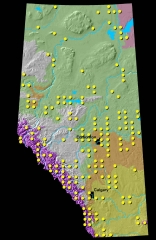

Found throughout Alberta, but not common in the southeast.

Habitat

Wild strawberries grow in open, well-drained places in lowland to subalpine zones. These plants can be found in fields and meadows, in disturbed areas, and in open forest.

How to Observe

If the plants are very abundant, mark a plot about one metre by one metre in size. 2. Record these dates:

- First bloom: When the first flowers are open in the plants or patch observed.

- Mid bloom: When approximately half (50%) of the flowers on the plants under observation are open.

When does this plant bloom?

Flowers in May, after spring thaw.

Life Cycle

The fruit represents the enlarged fleshy and juicy receptacle of the flower, with seeds borne in pits near the surface. Runners allow for vegetative reproduction, where the running stems root at the tips and produce new plants. Occasionally, some or all of the stamens (male parts of flowers) are sterile, producing no pollen.

The woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) frequently hybridizes with wild strawberry (F. virginiana), making some plants difficult to distinguish to species. The deeply pitted fruit in wild strawberry (F. virginiana) is one differentiating characteristic that appears to be consistent.

Ecology

Wild strawberry fruits are eaten by a number of birds and mammals, which disseminate the seeds in their droppings. Squirrels like to feast on the strawberries. Deer also favour the plants, and deer populations can have a major impact on growth of strawberries. First Nations Peoples on the west coast of British Columbia have noted that since deer were introduced on the Queen Charlotte Islands, the number of strawberry plants (likely the similar species, Fragaria chiloensis) has been severely reduced.

When the flowers are smaller than usual and greenish in colour, that is probable evidence that the plant is infected with a virus disease.

There are about 35 native species of Fragaria in temperate and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere and in South America.

Human Uses

A favorite fruit everywhere, wild strawberries are probably best enjoyed fresh, as a tasty bite along the trail. In the past, some First Nations Peoples have mashed the fruit spread out over mats to dry in the sun, but other groups considered them too juicy to dry. The flavour of the fruits is dependent on local conditions.

Strawberry flowers, leaves, and stems were also sometimes eaten. Strawberry-leaf tea is a good vitamin C supplement. It also has various medicinal uses. For example, the root is a strong astringent and is used as a treatment for diarrhea and other digestive orders. Herbalists suggest a tonic made from the leaves is good for the female reproductive system and to soothe inflammations of the skin and eyes. Large amounts of strawberry fruit in the diet is said to slow dental plaque formation. Ash made from the roots was mixed with

water to make a paste which was applied to open sores to facilitate the healing.

Young girls from one west native coast native group wore headbands and belts of strawberry runners plaited together in three or four strands. Today, the leaf essential oil is in demand for aromatherapy.

Wild strawberries are too small to compete with commercial hybrid strawberries, but remain a popular item with hikers and walkers.

Horticulture (Use in the Garden)

The common cultivated strawberry that is grown commercially and in gardens is considered to be of hybrid origin between the wild strawberry, F. virginiana, and the west coast F. chiloensis (L.) Duschesne. It was first developed in France and has been much improved by American breeders so that it is grown over a wider distribution than any other temperate-zone fruit. This hybrid species is the parent plant for 90% of the cultivated varieties of strawberries now grown. The wild varieties are easily grown and some believe the flavour is tastier than the domestic varieties. However, the domestic hybrids have larger fruits.

Quotes

“This berry is the wonder of all fruits growing naturally in these parts. It is of itself excellent: so that one of the chiefest doctors in England was wont to say, that God could have made, but God never did make, a better berry. In some parts where the Indians have planted, I have many times seen as many as would fill a good ship, within few miles compass.” (Roger Williams, an early colonist of Rhode Island, 1643)

References

Clark, L. J. 1976. Wild flowers of the Pacific Northwest. Ed. By J. Trelawny. Gray’s Publishing Ltd., Sidney, British Columbia.

Kershaw, L., A. MacKinnon, and J. Pojar. 1998. Plants of the Rocky Mountains. Lone Pine Publishing. Edmonton, Alberta.

Kershaw, L. 2000. Edible and medicinal plants of the Rockies. Lone Pine Publishing. Edmonton, Alberta.

Kindscher, K. 1992. Medicinal Wild Plants of the Prairie: An Ethnobotanical Guide. University Press of Kansas. Lawrence, Kansas.

MacKinnon, A. J. Pojar, and R. Coupe. 1992. Plants of northern British Columbia. B.C. Ministry of Forests and Lone Pine Publishing.

Marie-Victorin, F. 1964. Flore Laurentienne. Les Presses de l’Université de Montreal. Montreal, Quebec.

Marles, Robin J. et al. 2000. Aboriginal plant use in Canada’s Northwest Boreal Forest. Natural Resources Canada. UBC Press. Vancouver, British Columbia.

Porslid, A.E. and W. J. Cody. 1980. Vascular plants of continental Northwest Territories, Canada. National Museum of Natrual Sciences, National Museums of Canada. Ottawa, Ontario.

Roland, A. E. and E. C. Smith. 1969. The flora of Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia Museum. Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Scotter, G. W., H. Flygare. 1986. Wildflowers of the Canadian Rockies. Hurtig Publishers Ltd. Edmonton, Alberta.

Scoggan, H. J. 1978. The Flora of Canada. National Museum of Natural Sciences. Ottawa, Ontario.

Taylor, T. M. C. 1973. The rose family of British Columbia. British Columbia Prov. Museum Handbook No. 50 Victoria, British Columbia.

Tilford, G. L. 1997. Edible and medicinal plants of the west. Mountain Press Publ. Co. Missoula, Montana.

Torrey, J. and A. Gray. 1969. A flora of North America. Hafner Publishing. London.

Turner, N. J. 1987. Food plants of British Columbia Indians-coast peoples. British Columbia Provincial Museum. Victoria, British Columbia.

Turner, N. J. 1979. Plants in British Columbia Indian technology. Royal British Columbia Museum Handbook No. 38. Victoria, British Columbia.

Ward-Harris, J. 1983. More than meets the eye- the life and lore of western wildflowers. Oxford University Press, Toronto, Ontario.