Wolf Willow

Elaeagnus commutata – The flowers are very fragrant; and the beautiful striped seeds are popular in the Prairies for making necklaces.

Other Names

- in Latin: Elaeagnus commutata Bernh. ex Rydb.

- in English: silverberry

- in French: chalef changeant

The genus is derived from “elaia” meaning olive and “agnos” which is Greek for ‘chaste tree’, which has similar foliage.Commutata means ‘changed’, referring to the silver foliage which has “changed” from the normal green.

Taxonomy

Oleaster Family (Elaeagnaceae)

Description

A shrub, usually under 2 m tall, with rust coloured twigs.

- Leaves: Leaves are oval, 3 cm to 8 cm long, with a silvery-green colour.

- Flowers: Flowers are small (about 5 mm across), yellow on the inside and silvery on the outside, and produce a strong musky-sweet smell.

- Fruit: The fruit is a dry, silvery berry, with a large, stony seed marked with light yellow, striped grooves.

Distribution

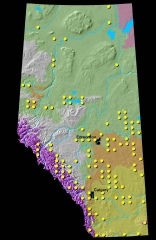

Found throughout Alberta, but most common from Edmonton southwards.

Habitat

Wolf willow’s habitat includes moister edges of prairies, dry hillsides and open fields in aspen forest. It is often found in overgrazed areas.

How to Observe

I. Tag a shrub for observation.

2. Record these dates:

- First bloom: When the first flowers are completely open in at least 3 different places on the observed shrub.

- Mid bloom: When half (50%) of the flowers on the shrub under observation are now open.

When does this shrub bloom?

Wolf willow flowers in late May to early June.

Life Cycle

Wolf willow fixes nitrogen, which in turn may allow it to survive on harsh sites. It can also be invasive, multiplying rapidly from a vigorous root system.

Ecology

Wolf willow has a partnership with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in root nodules and therefore enriches the soil. It does not form a closed canopy and competes little with surrounding vegetation.

The silvery sheen of this shrub is common throughout the prairies on coulees, cutbanks and hillsides. When the winter comes and the leaves have fallen off, the silver berries continue to stand out against the white snow and bright blue prairie skies.

Though commonly called wolf willow, this plant species is not a willow at all. Instead, it belongs to the Elaeagnaceae (Oleaster) family and is related to thorny and Canada buffaloberry (Shepherdia).

Phenology

Flowers appear usually from late May to early June. Fruits ripen between July and September. Seeds often stay on the plant through the winter.

In her book, Old Man’s Garden, Annora Brown wrote, “wild roses and silver willows abloom on the banks of a stream over-flowing with melted snow and yellow mud, mean that summer has come at last to the prairies”.

Human Uses

Wolf willow berries were used by Blackfoot Natives to make seed necklaces. The berries were boiled to remove the flesh and the pointed nutlets strung onto necklaces or used to decorate the fringes on clothing. Each seed is dark brown with yellow stripes. When the first settlers arrived, the women quickly learned the art from the natives, and wolf willow seed necklaces became a popular gift to send home.

The bark was used to make strong fibre baskets useful for collecting berries. Bark was also used to make cordage. Native people discovered the bush had a bad smell when burned. Those who used it for firewood were chided for being lazy.

Wolf willow fruit is mealy and dry, but was still eaten by some First Nations. Blackfoot Indians peeled and ate the berries or mixed them with grease and stored them in a cool place. This was eaten as a confection or added to soups and broths. The berries were sometimes mixed with blood or sugar and cooked for food. Children suffering from frostbite were treated with a strong solution made from the bark.

The essential oil is in demand for aromatherapy.

Horticulture (Use in the Garden)

The silverberry is frequently grown in the garden as an ornamental shrub.

References

Brown, A. 1970. Old Man’s Garden. 2nd edition. Evergreen Press Ltd. Sydney, British Columbia.

Cormack, R. G. G. 1977. Wildflowers of Alberta. Hurtig Publishers. Edmonton, Alberta.

Hellson, J. C. and M. Gadd. 1974. Ethnobotany of the Blackfoot Indians. National Museum of Man Mercury Series, Canadian Ethnology Service Paper No. 19. Ottawa, Ontario.

Marles, R. J. et al. 2000. Aboriginal plant use in Canada’s Northwest Boreal Forest. Natural Resources Canada. UBC Press. Vancouver, British Columbia.

Moss, E. H. 1983. Flora of Alberta. 2nd edition. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, Ontario.

Vance, F. R., J. R. Jowsey, and J. S. McLean. 1977. Wildflowers Across the Prairies. Western Producer Prairie Books. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.